In September 1969, The Architectural Review launched Manplan: a humanist manifesto with the aim of re-evaluating, from the ground up, the needs of the public and the ways in which architecture might provide. The title served as a reminder, 'to the editorial staff as well as the reader, that this enquiry is angled at achieving within the resources available what our society needs most rather than what will pay best’.

The campaign started with Frustration, a photo essay stretching its limits out to take up a full issue with the ills befalling the British public. Photographer Patrick Ward was commissioned to document a month’s worth of frustrations for the issue, all recorded on grainy 35mm film and blown up to fill the spreads from bleed to bleed, or else to be placed as small squares in a scorching sea of matt-black ink.

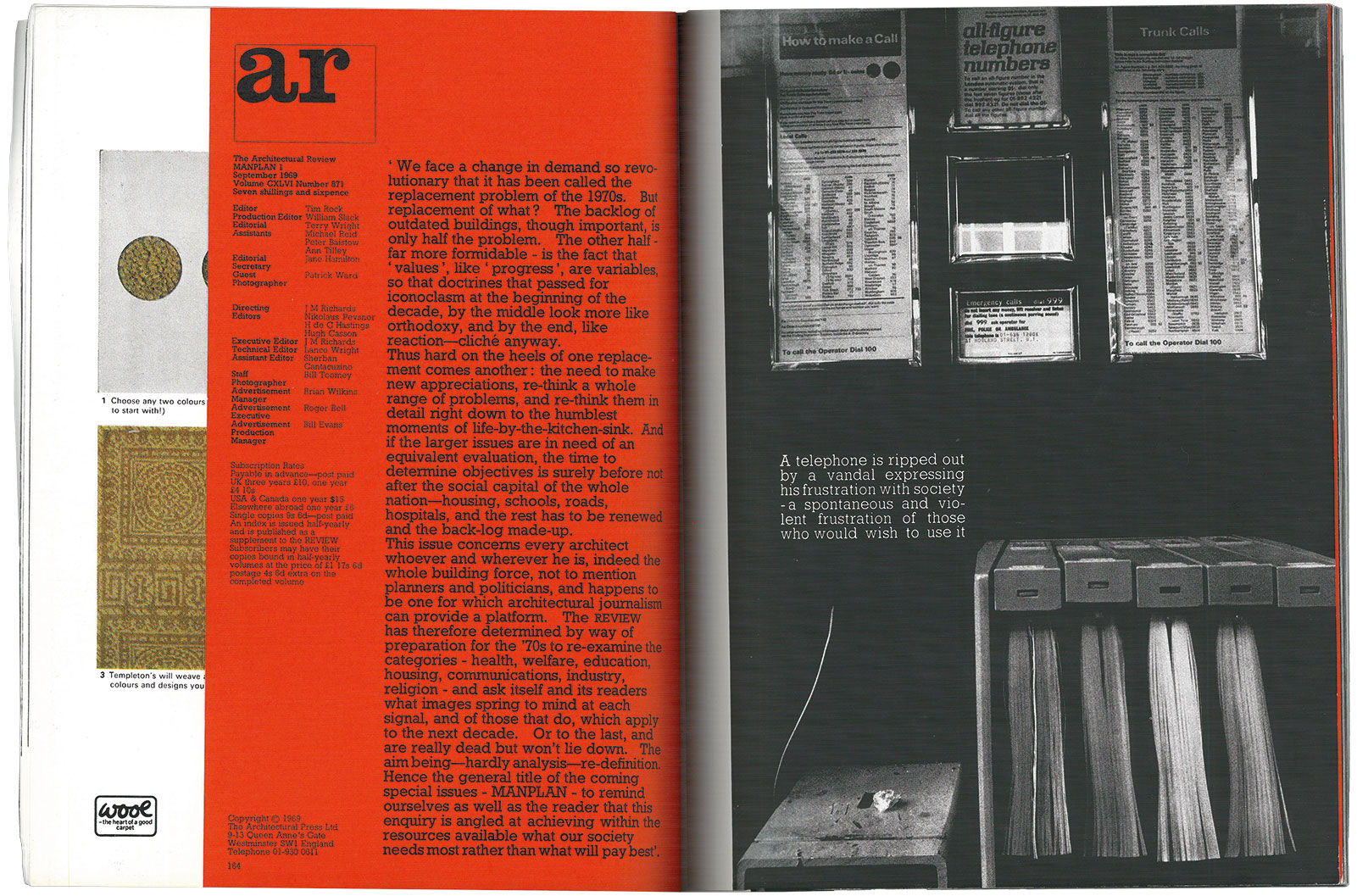

A telephone is ripped out by a vandal expressing his frustration with society – a spontaneous and violent frustration of those who would wish to use it

The issue pointed at problems rather than offering solutions, with offerings of text limited to openings, conclusions and short, incisive captioning. Aside from quarrels with queueing and commuting, the issue examined a nation in strike, lingering over the state of schooling and the provision of welfare. ‘The picture that emerges’, as the editors wrote, covering ‘the whole spectrum of despair from inconvenience through exasperation to tragedy and, of course, farce’

The AR had called into question, in ardent fashion, what exactly architectural publishing was for, and the ends to which its platform could be extended as a political tool. The issue, along with the campaign that followed, was deeply unpopular. The particular reasons why this call-to-arms had fallen short of stirring the heart of every architect who found its pages can be left to the imagination. But we are certainly left with the lasting sentiment: frustration remains.

‘In this and succeeding months the AR tries to prepare for the ’70s and beyond – the last third of the twentieth century – by reviewing the state of the nation in those areas where it has a patent to speak – architecture and planning. A tall order, made taller by the necessity for the planner to redefine his terms. Housing for instance. Is current housing policy sound and if so will it be valid for the next decade? Or religion. What future is there for churches as buildings in terms of social – and thus town – planning?

‘Here, as elsewhere, appears the eternal confrontation between the feasible and desirable, what can and what cannot be done. The REVIEW has not exactly plumped for the unobtainable but it has rejected the conventional wisdom. Instead it takes as its yardstick real needs rather than minimum standards. Hence the title Manplan. A plan for human beings with a destiny rather than figures in a table of statistics.’

‘Why bother when we are told continually we’ve never had it so good? Because, though modern man is in some ways wealthy beyond dreams, in others he’s never had it so bad. The reader is invited to leaf through the pages that follow and ask himself whether the consumer society is not paying too high a price for affluence in the pressures and frustrations which seem to dog the footsteps of every technological advance.

‘The question is are they the inevitable fringe benefits? Or is there a gap in our thinking? Is technology for us or against us? Manplan proposes in the next few months to consider these matters in depth in the hope of coming up with some answers, but here forget technology and turn to the subject of this issue, the built-in spirit of defeatism which makes all our frustrations possible, since, like built-in obsolescence, it predetermines the end. We only skim the surface, but the picture that emerges covers the whole spectrum of despair from inconvenience through exasperation to tragedy and, of course, farce.’

The Architectural Review An online and print magazine about international design. Since 1896.

The Architectural Review An online and print magazine about international design. Since 1896.