A highlife song by Ghanaian band Wulomei is a valuable record of the now-dilapidated Meridian Hotel in Tema New Town

Listen to this podcast on your platform of choice

In this episode, architect, artist and critical urban theorist Dele Adeyemo takes us to the modernist Meridian Hotel in Tema New Town in Ghana. The 1975 song Meridian by Ghanaian group Wulomei provides evidence of its former grandeur and the ambition of post-independence Ghana – evidence that cannot be found in traditional archives.

This AR Bookshelf episode is part of a collaboration between The Architectural Review and the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) around the book Fugitive Archives: A Sourcebook for Centring Africa in Histories of Architecture, published following the CCA’s Centring Africa research project. In each episode of this short series, a researcher from the publication tells the story of a place based on sources traditionally overlooked by western archives. Forming a fugitive archive itself, the episodes study both the places themselves and the media – better suited to podcast than paper – that document and describe them.

Fugitive Archives is edited by Claire Lubell and Rafico Ruiz, with graphic design by by Naadira Patel and Fred Swart and co-published with Jap Sam Books (October 2023).

This is an edited version of the episode introduction.

Listen to other episodes, including from the AR’s collaboration with the CCA and the AR Bookshelf series

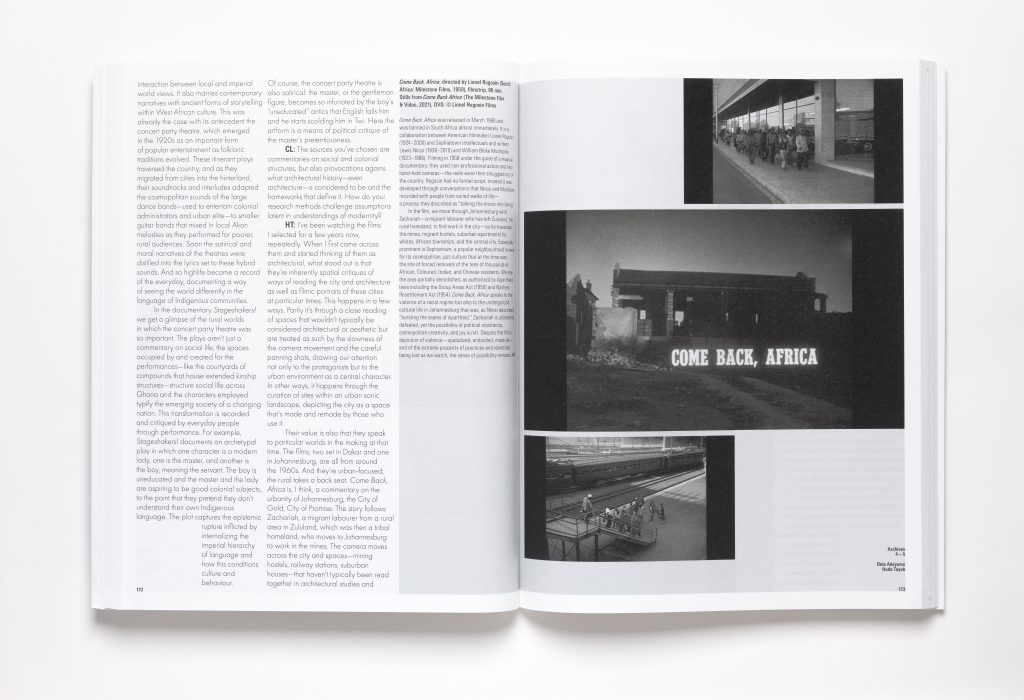

The concrete shell of the dilapidated Meridian Hotel in Tema New Town, Ghana

Credit: Joseph Bawa / Alamy

Transcript

Dele Adeyemo: The musical genre of highlife – a cosmopolitan, future-oriented West African sound – came to prominence in Ghana in the lead-up to and following independence in 1957. Long before the prominence of Afrobeats in today’s popular culture, highlife’s modernising beat filled the airwaves of the newly independent Ghana Broadcasting Corporation Radio and the recently constructed bars and dance halls of the industrialising society. It provided a West African flavour to what the British-Caribbean cultural theorist Paul Gilroy coined as ‘the Black Atlantic’ – describing the transatlantic exchanges and cultural hybridisations that produced a modern Black global culture. Highlife was the sound that defined the era and rhythm of post-independence society in Ghana.

The highlife song Meridian, by the band Wulomei, celebrates a product of this post-independence era. The song is about a five-star luxury hotel opened in 1960 by the first president of Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah, in Tema, one of Africa’s first modernist New Towns. The Meridian Hotel sported a helicopter landing pad, lifts and swimming pools, and was the grandest in a series constructed by the Ghana State Hotels programme to accommodate a cosmopolitan clientele encompassing local workers, entrepreneurs, politicians and international dignitaries and industrialists.

‘As is so often the case with architectural archives in Africa, the record is missing or incomplete’

As I searched what records are left from this period in Ghana’s public archives in Accra, and scoured the architectural plans in the archives of the Tema Development Corporation, I could find nothing of any note about the Meridian Hotel. I am yet to find any evidence of who designed the building, though it is likely to have been designed by Eastern European architects. As the architectural historian Łukasz Stanek has highlighted, much of the architecture in Ghana from this period was heavily influenced by Soviet and other Eastern European designers, as Nkrumah nurtured relationships beyond western nations as part of his policy of non-alignment.

As is so often the case with architectural archives in Africa, the record is missing or incomplete. Even if I had found information on the hotel, it would not have spoken of the perspectives of everyday people about the significance of this development. But if we listen carefully to this track by Wulomei, something is revealed about the worlds that this building straddled. Rising above the highlife melody, a young woman’s voice in the local language of Ga can be heard singing:

There’s a certain gentleman from Sempe.

He is such a good-looking man,

and gives unconditional love.

He came around to wake me from my sleep.

I asked him, ‘What is the matter?’

He told me, ‘I’m in a hurry’…

And I asked him, ‘Where are you taking me in such a hurry?’

‘We’re going to the Meridian in Tema,’ he said.

‘We’re going to dine, drink and dance.’

In her words, the protagonist makes the literal journey from the Ghanaian village of Sempe to the city of Tema, which acts as a symbol of the journey that many people of her generation were making at that time in the 1970s, a passage from rural settlements to urban environments, bringing with them modern ways of living. In the lyrics we can hear both the tension and excitement of this moment.

The Meridian Hotel was constructed on the edge of the industrial zone of Tema Harbour and Community Number One, one of the first residential areas built as part of the 25 planned communities based on a masterplan by Greek architecture and urban design practice Doxiadis Associates. Tema Harbour and Tema New Town were intended as a critical spaces in the transformation of Ghana into a modern industrial economy, with the Meridian Hotel as the centrepiece in the development.

Where traditional systems, such as the coastal fishing societies found at the site of Tema Harbour, stood in the way of development, they were swept aside. President Nkrumah believed that the transformation of Ghana’s economy necessitated the invention of a new cultural identity epitomised by what he termed the ‘African personality’ – an idealised citizen who combined the lifestyles of the industrialised workforce and the nuclear family structure of the global north, with selected African traditions in music and culture. The Meridian, like the other hotels constructed during this period, became an important symbol of the comparative luxury of modern architecture, where the worlds housed within its sleek white concrete walls allowed the wider public to see and participate in aspirational modern lifestyles.

‘I’m told that the spirits will never allow a successful development to happen there’

Today, all that remains of the hotel is a hollowed out concrete skeleton that looms over Tema Port. The site is now owned by a foreign investor and despite periodic press releases about renovation plans, the building remains derelict. These days, only criminals and desperate squatters go anywhere near. Large sections of the structure regularly collapse, crashing to the foot of the tower as the decomposing concrete frame is licked by the tropical sea breeze. Local mythology describes the development as cursed because it was constructed on sacred land that was expropriated by the newly established state. I’m told that the spirits will never allow a successful development to happen there.

In the shadow of the tower, in what would have been the forecourt, stands a baobab tree, wrapped in a white cloth to signify its sacred status to the community. The tree appeared on this site centuries before the hotel was built and has been worshiped by generations of people living in its vicinity. Despite Nkrumah’s efforts to sweep aside tribal cultural identities and replace them with a modern archetype fit for an industrialised nation, the site continues to host annual spiritual festivals. Like a decayed physical representation of Le Corbusier’s Dom-Ino House, the Meridian stands as a monument to the faded dreams of tropical modernism and the now distant promise of post-independence West Africa.

The AR depends on its subscribers to bring you fearless storytelling, independent critical voices and thought-provoking projects from around the world. Consider supporting the AR with a subscription today, students receive 50% off

The Architectural Review An online and print magazine about international design. Since 1896.

The Architectural Review An online and print magazine about international design. Since 1896.