Smuggled out of South Africa, the film Come Back, Africa provides evidence of the life of since destroyed Sophiatown

Listen to this podcast on your platform of choice

In this episode, architectural historian, writer and educator Huda Tayob takes us to the now destroyed Sophiatown in Johannesburg, South Africa, through recordings of the neighbourhood found in the 1959 film Come Back, Africa.

This AR Bookshelf episode is part of a collaboration between The Architectural Review and the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) around the book Fugitive Archives: A Sourcebook for Centring Africa in Histories of Architecture, published following the CCA’s Centring Africa research project. In each episode of this short series, a researcher from the publication tells the story of a place based on sources traditionally overlooked by western archives. Forming a fugitive archive itself, the episodes study both the places themselves and the media – better suited to podcast than paper – that document and describe them.

Fugitive Archives is edited by Claire Lubell and Rafico Ruiz, with graphic design by by Naadira Patel and Fred Swart and co-published with Jap Sam Books (October 2023).

This is an edited version of the episode introduction.

Listen to other episodes, including from the AR’s collaboration with the CCA and the AR Bookshelf series

Johannesburg captured in the 1959 film Come Back, Africa

Transcript

Huda Tayob: Film might offer footage and sounds of cities and urban sites at a particular time. Yet, beyond a record of place, film is an important site of archival imaginaries, provoking questions not only around what was, but what might have been.

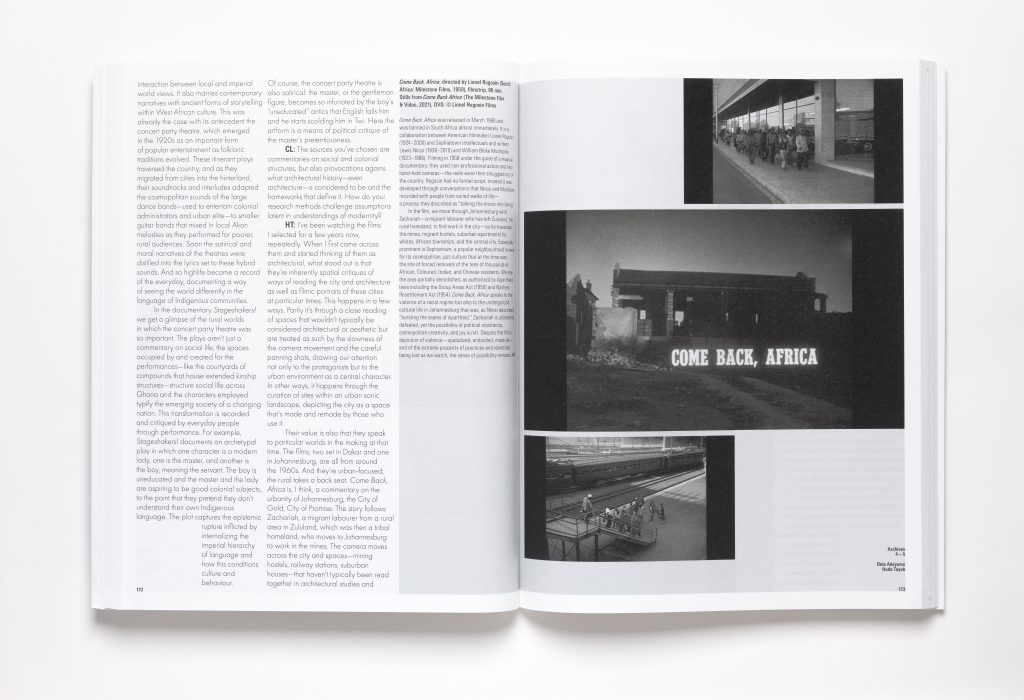

Come Back, Africa is a 1959 film which can be read as an undisciplined urban history of Johannesburg, South Africa. The film was a collaborative project between American filmmaker Lionel Rogosen and two established intellectuals and writers – Lewis Nkosi and William Bloke Modisane – who hailed from Sophiatown, a Johannesburg neighbourhood at the centre of apartheid oppression and the Johannesburg jazz and cultural scene. In the film, we journey through Johannesburg with Zachariah Mgabi and later his wife Vinah. Mgabi is a migrant labourer who has left his rural home in the South African Bantustan of Zululand in search of work in the city. The central narrative is framed around his experiences and the many difficulties he faces in navigating the apartheid urban environment.

Film footage: ‘You always blame the train; why don’t you get up in time to catch the train?’

Huda Tayob: We travel with him through mines and migrant hostels, a hotel, a white suburban apartment, a road construction site, the central city, domestic servant quarters, train stations and a series of very different kinds of street. These spaces include domestic homes and shebeens – or informal bars and gathering spaces – in Sophiatown, an area of Johannesburg well known for its cosmopolitan jazz culture, and at the time of filming, in the process of being demolished under a series of apartheid laws which enforced racialised displacement and segregation across the country. These regulations supplemented, extended and built on various public health and hygiene laws, and slum clearance declarations from at least the early 1900s. Apartheid was a system of governance instituted in 1948 by the Afrikaner Nationalist Party, yet in many ways it enacted a continuation and consolidation of racialised colonial planning laws.

Still from the film depicting a train station

That Sophiatown was completely destroyed soon after filming makes the argument that this film is an important archive of a particular time and place almost self-evident. Yet this immediately begs the question of why it is not more present in urban histories. The film was made with non-professional actors, mostly filmed with two handheld cameras, with the reels smuggled out of the country as they were being shot.

There was no formal script; the outline was developed through a series of recorded conversations led by Nkosi and Modisane. In a 1960 article in the publication series Fighting Talk, an anti-apartheid magazine, Nkosi talks about the process of making this film, describing how, together with Modisane and Rogosen, they would travel around the townships of Johannesburg with a tape recorder, listening and speaking to people. He says, and I quote, ‘It was in these small gatherings that people often revealed more poignantly their innermost fears. It was also during this preparatory stage of the film that we found the work stimulating in a very creative sense’, end quote.

‘The city and its spaces are not merely incidental background to an anti-apartheid political film here’

The various sites in which the narratives take place suggest a reading of the urban as intimately entangled, and not a series of separate worlds as we have largely been led to understand apartheid South Africa. In the adjacency of domestic, infrastructural and public sites we are being asked to understand the city as consistently co-produced by its diverse populations, who continuously cross the social and spatial divisions that were being implemented and enforced. We are confronted with both the intimacy and violence of segregation.

The city and its spaces are not merely incidental background to an anti-apartheid political film here; instead we are asked to read urban Johannesburg again, through its many street, interiors and infrastructures, alongside its various associated debates. Together these speak to how people constructed their own urban environments and their own urban narratives.

This is particularly notable in several fairly long four to seven-minute scenes, where we are simply watching the life of the street along with various other sidewalk spectators. In Sophiatown we hear a funeral parade, a wedding procession, penny whistle groups, a street theatre setting up and people outside trying to get a glimpse of what was happening. We hear a brass marching band and we follow church groups along on the street. With the various spectators in the film who stand on the sidewalk or watch from their verandas, the audience pauses to listen. To listen and watch the city.

The rubble of Sophiatown is captured on film

And in these scenes, we see the piles of rubble. Some people sitting with all their household goods among demolished houses. Chickens and horses. Children playing amid ruins. We see the traces of graffiti: ‘we will not move’ and ‘hands off western areas’. And sometimes just people chatting. Store windows. People arguing. People dancing. Some fights. Sometimes we follow the protagonists. At other times, we just follow the street.

Part of this footage can be explained by the official reasoning for the film as a musical documentary. Yet, in these longer street scenes, the filmmakers ask for an engagement and reading of and with the street across the city. They present the vitality and ordinariness of street life. This is not a romanticised nor nostalgic view of streets that were in the process of being destroyed. Visually and sonically, this is instead an argument for the presence of Black urban life against the claim – at the time – that it did not exist.

Messages of protest are visible on the buildings as the audience watches the protagonists walk the streets

As Nkosi has written about the production of the film, and I quote: ‘Some scenes of urban life that we used in the film sequence were conceived in the shady Sophiatown shebeens amidst a hubbub of talk, cigarette smoke and that thick, bitter-tinged laughter that was so peculiar to the groups with whom we got involved.’ As he describes, ‘they talked the movie into being.’

One shebeen scene in the film is an extended conversation between Nkosi, Modisane and the writer Can Themba, and with a performance by Maria Makeba. This conversation centred on a debate of questions of violence: township violence as well as apartheid violence.

Film footage: ‘If you had to fight him back you should’ve finished him!’ ‘But I never finish anybody – I never kill anybody.’

Huda Tayob: The violence of liberalism, the violence of good intentions, of trying to solve problems over a cup of tea. It is a deliberation on the state of South Africa, on the question of land, on the possibilities of creative work for enabling or crossing borders, constructing different forms of belonging that exceed the national and ethnic.

Film footage: ‘If I could get my worst enemy over a bottle of beer, maybe we could get at each other! It’s not just a question of just talking to each other but it’s a question of understanding each other, living in the same worlds.’

Huda Tayob: It is an ethical debate about what it means to live with and through violence. It is also a moment of joy. Where, as the authors note, despite this violence, this was a time when cultural life in Johannesburg was bursting the seams of apartheid.

While the central characters in the film were ultimately defeated, the overlapping possibilities of political resistance and cosmopolitan creativity were not. And it is this complexity of urban life that the film portrays so clearly, as spatialised, embodied and material. The depiction of extreme precarity and violence of that which was being lost as it was being filmed and written about does not preclude a sense of what might still be possible. This work points to ways in which the city is being negotiated, debated and discussed in creative experiments and through intellectual debates. In the deliberate moves between documentary and narrative, fiction and history, we not only view these kinds of sources as an archive of the city, but also as a site from which we might question the production of historical narratives.

The AR depends on its subscribers to bring you fearless storytelling, independent critical voices and thought-provoking projects from around the world. Consider supporting the AR with a subscription today, students receive 50% off

The Architectural Review An online and print magazine about international design. Since 1896.

The Architectural Review An online and print magazine about international design. Since 1896.