A collective and generous spatial practice sits at the heart of Himid’s retrospective exhibition, asking who designs our spaces and for whom

‘We live in clothes, we live in buildings – do they fit us?’ Lubaina Himid asks on entering her retrospective exhibition, at the Tate Modern until 2 October 2022. Bodies inhabit buildings in the same way they inhabit clothing: ‘It fits where it touches, beware chafing and rubbing.’

An engagement with architecture – as a spatial practice that can be simultaneously collaborative, emancipatory and fraught – guides many of the works in Himid’s latest exhibition, as well as the conception of the exhibition itself. The exhibition is performed specifically within the galleries of the Tate Modern’s Blavatnik Building: the ‘scenery lift’ is recast as the backstage for A Fashionable Marriage (first shown in 1986), from which the messy assembly of each set piece is revealed; and a surreal bike shed / smoking area (Do You Want an Easy Life?, 2021) marks the exhibition exit.

A Fashionable Marriage (1984-6, 2017, 2021) © Tate / Sonal Bakrania

Buildings are literally depicted in several of the artworks – the insular curved form of Country House (1997), the inhabited still-life East West Wing (1997) and beautiful campanile and palazzi of Garfoni (1995) – and the Jelly Mould Pavilions for Liverpool from 2010 comprises models for a possible monument for the city (one of which was realised as a full-scale pavilion at the Folkestone Triennial 2017). But the practice of architecture, rather than its built forms, is explored more closely in a series of recent paintings where the buildings themselves are not always centre stage.

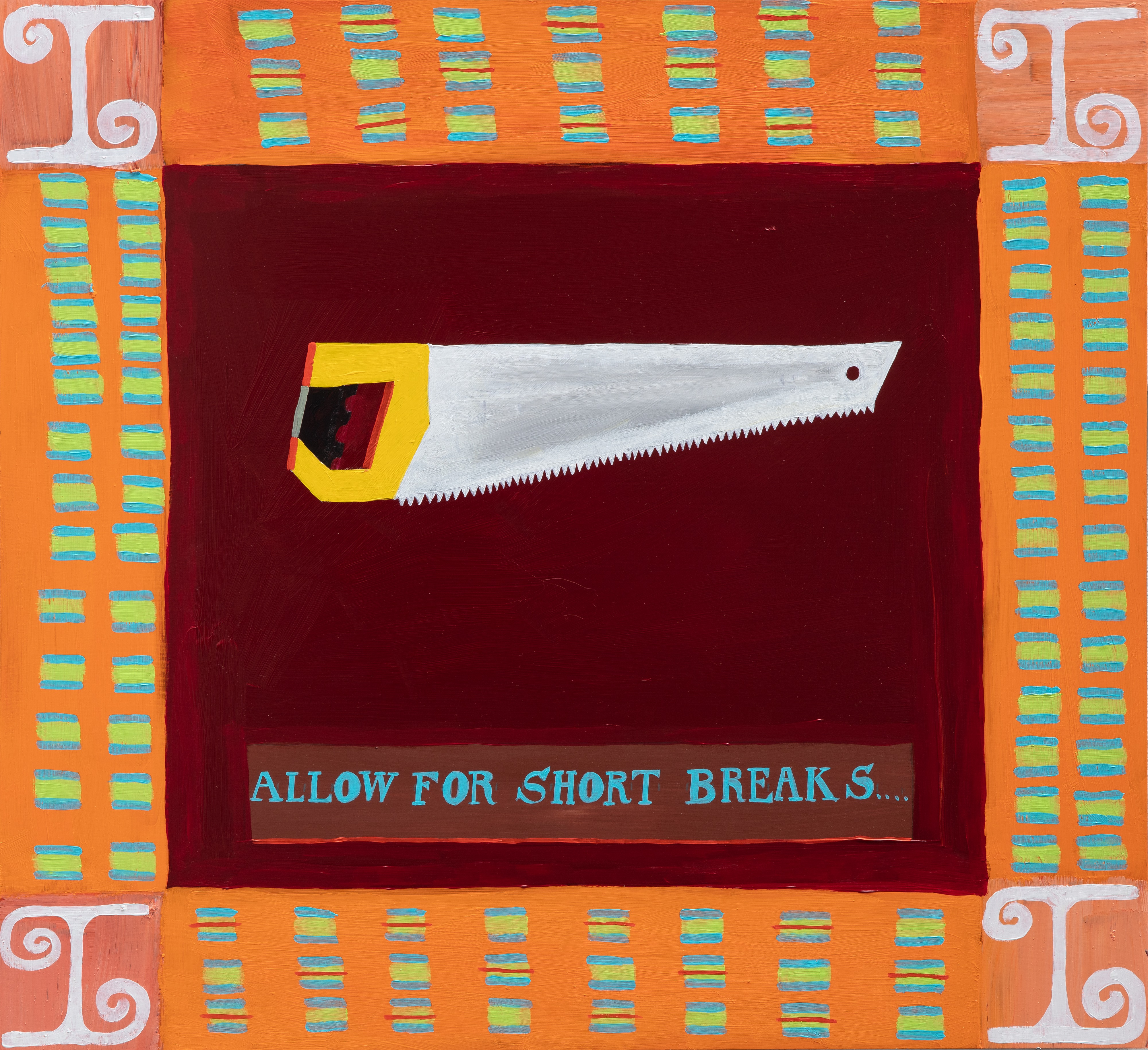

On entering the exhibition, the Metal Handkerchief series (2019), inscribed with instructions originally from health and safety manuals, invites visitors to ‘ensure sufficient slack’, ‘keep moving parts lubricated’, and ‘give warning of undue strains’. We are provided with the tools: a chisel and pulley to ‘work from underneath’, a lethal-looking saw and small flags to ‘allow for short breaks’, a wood plane and a rope to ‘ensure sufficient space’. The spaces Himid encourages us to attend are both the buildings and cities we inhabit and the space of our bodies – the armatures we might be trapped within, are weighed down by and carry with us. Himid situates maintaining both physical and mental wellbeing as a spatial practice: chiselling away restrictive edges, loosening screws, releasing tension, making fit.

Saw/Flag (2019), from the Metal Handkerchief series. Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens

Both architects and tailors are ‘tasked with creating liberating spaces within which the body can thrive’, as Amrita Dhallu comments in the exhibition catalogue. In Six Tailors (2019), it is Black men who are caught in the flurry of designing and creating. Hands and eyes cross and brush each other with the familiarity of close collaborators, the cooperation frictionless. The workshop is a construction site for bodies and alternative futures; the table is strewn with fabric, scissors, cotton reels and cut-out pattern paper. It could almost be a model of a city, the ream of blue fabric a river, the cotton reels small housing blocks, the checked fabric a net of roads. This textile architecture is woven from the threads of stories and histories, of the people whose hands weave them together: a situated practice shaped by the multiple positionalities of its authors.

Six Tailors (2019)

‘Himid situates maintaining both physical and mental wellbeing as a spatial practice: chiselling away restrictive edges, loosening screws, releasing tension, making fit’

Himid is interested in architecture as a collective and contingent practice – one of conversation and negotiation. In Three Architects (2019), a pair of women stand at the centre of the studio in discussion around a model on a small high table, a third architect at work in the background. The studio is depicted as a place of play, experimentation and plural practice: eight models are dotted around the room, each unique and apparently unrelated to the others. A white thread winds across the ground, connecting the three architects in their common endeavour: ‘The women do things together,’ Himid explains, ‘not always in the same way but usually for the same reasons.’ This is an architecture of multiple authors, many hands and varied manifestations, but with a shared commitment to collectivity.

Three Architects (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London. Photo: Dario Lasagni

The table recurs in Himid’s work as a site for exchange, creativity and dialogue. In Three Architects, the discussion appears to be collaborative and constructive. One architect points to the model, the other arm resting in familiar intimacy, her colleague holding her hand to her mouth in careful thought. In Five (1991), on the other hand, the two women across the table from each other are confrontational – no agreement can apparently be reached. The reason for their animosity is played out on the table between them: a geopolitical map with the continent of Africa painted on a plate to the right (the east), and the stars and stripes of the US Star Spangled Banner on a plate to the left (the west). A sugar bowl sits in the middle, a trail of white sugary dots suggesting a path across the table between the two plates, and with it the link between sugar and slavery and the Tranatlantic routes between the US and Africa.

Five (1991). Courtesy of Grisselda Pollock and the artist / Bridgeman Images

The ocean is implied between the plates of Five; in Three Architects (and in countless other works) the sea is more explicitly present. A horizon of water sits ominously high in the windows of the architects’ studio, scudded with white waves. As Michael Wellen notes in the exhibition catalogue, for Himid the ocean is both ‘a site of pleasure – for holidays and childhood play’, but also of violence – across which African people were forcibly transported and where they were enslaved. ‘How terrifying would this be,’ Himid asks herself, ‘to be in a place with five hundred people … in a moving, stinking space, not knowing that it’s a wooden sailing ship, on this stuff that I don’t know is the sea?’

The history of slavery and colonial power threads through the work of the exhibition. Himid was born in Zanzibar in 1954, then a British protectorate, and moved to the UK as a baby. The city of Zanzibar itself was segregated along racial lines in 1923 following British architect Henry Vaughan Lanchester’s masterplan and has been subject to a raft of further masterplans by foreign powers, both before and after independence in 1963. In The Operating Table (2019), it is not white colonisers who are crowded around a masterplan, but three Black women. On first appearances, the painting gives agency to these women to design a city, radically repositioning the traditional authorship of the urban places we inhabit. There is, however, a feeling of unease between the three protagonists: the character on the right points forcefully at a body of water on the plan while the central character has one arm crossed defensively and the woman on her left leans away with a die in her hand, proposing perhaps that the design of the city should be left to chance.

The Operating Table (2019) © Lubaina Himid

The protagonists’ disquiet is understandable: though the masterplan resembles the vivid and organic landscape plans of Roberto Burle Marx more than the bloodless developer-led visions we might be familiar with in the UK, in its zoning – with areas of forest, agriculture and buildings clearly demarcated by geometric arterial roads – and the setting of isolated buildings in large fields of green, there are also overtones of the modernist colonial masterplans proposed in Africa in the last century – including in Zanzibar. The painting disrupts a canon of European portraiture in which white male colonists are depicted with one lazy hand sprawled over a map of the territory they were in the process of violently settling. Dhallu sees in the masterplan that Himid’s protagonists are ‘refusing the western cartographic principles of divide and conquer’ and ‘developing instead an embodied governance of land, using the swooping contours of the natural topology to guide them’. Another view is that the plan, and the act of designing such a plan, in fact replicates many of the tropes of modernist masterplanning – an expansionist and colonial tool – and that these characters are in uncomfortable dissonance with each other and their task, reluctant to fill the role of the authoritarian urbanist.

Colonial British masterplan for Zanzibar, designed by Henry Kendall and Geoffrey Mill in 1956

The Operating Table and Three Architects are in many ways scenes familiar to architects, in the close collaboration and fruitful exchange they depict. However, in a UK context, Black and female architects are few and far between (two-thirds of registered architects in the UK were white men in 2019 and just 1 per cent were Black). Himid asks who designs our spaces and who do they design them for: ‘What kind of buildings do women want to live and work in?’ she asks. ‘Has anyone ever asked us?’ The characters in Himid’s work not only have a seat at the proverbial table – in a way they are systemically denied across the country – but also crucially have agency and engage in dialogue at that table, making decisions, and being heard. Himid invites you to join the conversation, to draw up a chair, to hear what is said and give your own opinion. Take a seat.

Lubaina Himid’s retrospective is at the Tate Modern in London until 2 October 2022

The Architectural Review An online and print magazine about international design. Since 1896.

The Architectural Review An online and print magazine about international design. Since 1896.