Singapore has reached the crisis of its perfection

Many people apparently dream about the Queen of England, but probably more have fantasies about Singapore, its extraordinary success over 50 years of being an independent state, and its problems as a corporate state. Singapore Inc, like iconic buildings sprouting over the globe, is a living Rorschach test. Foreigners project their wishes and fears onto the city-state. Some claim it is the ‘only city in the world to grow greener as it grows bigger, richer and denser’; others believe William Gibson’s infamous jibe that it is ‘Disneyland with the Death Penalty’. Such generalisations are invoked by outsiders, even those resisting the lure of stereotype. In 1995, Rem Koolhaas lamented the way Westerners pigeonhole the Modernist city with ironic labels such as Theme Park – and then immediately did the same with his ‘Portrait of a Potemkin Metropolis’. Like a good Rorschach blob, the city provokes a response, revealing some truths, though these often tell you more about the viewer than the viewed, as the famous Swiss inkblots should.

I will be looking here both at the paradoxical city-state and the reigning style of Generic Individualism that dominates global cities today; examining a few starchitects and their iconic buildings, and the way we project meaning onto their enigmatic constructions. Singapore and icons both elicit a seductive power, an anger or joy to which I am not immune. But my purpose is to augment a thought experiment (or gedanken as Einstein called it) that the Singaporeans are having, and to use architecture to think it through: can the city take the next step?¹

‘Some claim Singapore is the only city in the world to grow greener as it grows bigger, richer and denser, others believe that it is ‘Disneyland with the Death Penalty’

Socitalism – socialised capitalism?

When Singapore was forced to go it alone by surrounding countries and become a city-state, the quandary was put clearly by its founding leader Lee Kuan Yew. Independence, he said, was ‘a political, economic and geographic absurdity’. One absurdity was the lack of resources and drinkable water on the very hot equator; another was the fractious mix of ethnic groups. Dr Liu Thai Ker, director of RSP Architects and head of the Housing & Development Board (HDB), put his finger on this problem and tied it to the omnipresence of slums: ‘In 1960, around the time of our independence, Singapore had 1.89 million people, and roughly 1.3 million lived in squatter huts. Squatter huts were single-storey sheds constructed with cardboard, zinc sheets, sticks and poles, with no modern sanitation treatments, and with limited electricity and water supply … there was only a weak sense of nationhood. If you asked the Chinese where their home country was, they said China. If you asked the Malays, they said Malaysia. If you asked the Indians, they said India. So how can you build a nation under such circumstances?’²

For Singapore there were two answers, two ways to form a nation. The first was the Modernist way – that is, universal progress for most of the population, a general increase in prosperity, one that cements national unity. Singapore in the last 50 years has grown faster and more continuously than most other countries – such as the United States, Japan and China – and now it has one of the highest GDPs per person at $50,000 per year (though this is skewed upwards by the very rich few. The second answer was the Postmodern reply: a pluralism of choice for almost everyone, a choice that acknowledges ethnic and individual identity, particularly one helped by the computer, that is, mass customisation.

Diagram 1 Charles Jenks Essay

Both answers worked together to supply a kind of proto-nationhood, although, as is said, money isn’t everything and market pluralism is not the real thing. Yet both lowered the temperature of fractious groups, just as mass air conditioning raised living standards.

The claims to Modernist universalism are quite different from those in Britain. After 50 years of high economic growth, varying between two and nine per cent a year, 70 per cent of the population has now become, in important ways, like the top 30 per cent. Public housing, or ‘the HDB’, exists for more than 80 per cent (one of the highest percentages in the world) and it is accompanied by four other public amenities: good transport, good education, good health and good living in a green city for everybody (except when polluted by neighbours). Above all, this modernisation is the ‘leap-frog economy’ as it is called, where the government pushes business into new technical sectors before they have boomed, and back out, before they go bust. This directed growth supplies – for hard-working people – some good and fast-changing jobs, and high social mobility. But it leads to pervasive anxiety, as Liu Thai Ker pointed out at the World Architecture Festival in 2015: it leads to ‘perfectionitis’, one of several maladies I will be treating, below.

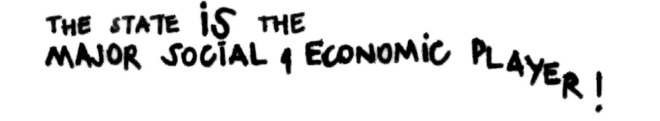

Singapore Charles Jenks essay

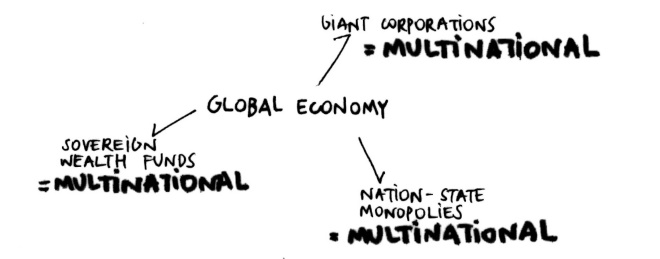

In important ways the developed world has also gone through a similar disruptive progress, and similar stages of economic growth. Yet in the West, the social transformations were over hundreds of years, not 50, as my diagram (page 55) shows. In the West, mercantile capitalism of the 16th century led to industrial and then monopoly capitalism in the 19th century, and then to welfare capitalism after the Great Depression. This culminated in what I have labelled ‘socitalism’. I will invoke more ‘isms’ later, some more coherent and defensible than others, but all of them are necessary for thinking about the evolution of society and architecture (you can’t think without pigeonholes). For instance, on the middle right of the diagram are the mixed economies of Modernism (what is now called ‘Fordism’, or mass production); above it is the mass-customisation of Postmodernism (or ‘Post-Fordism’ – terms that became standard in the 1980s). These production systems are mixed in with socialised investment (bottom of the diagram). This last area tended to be parts of the welfare state in the 1930s, or Military Keynesianism since the Cold War, where the socialism consists, ironically but pragmatically, of huge standing armies and military investment – typically that of China and the United States.

My diagram emphasises the whole vertical mixture as today’s reigning, yet apparently invisible, socitalism (that is, socialised capitalism) and I have argued, since 1995, that people were wrong to say we live in a simple capitalist world (as if the state were not the major social and economic player). Or, they become ideological to imply we are living in 1750s Glasgow, when small-scale competitive capitalism did exist, as Adam Smith described it. Instead, the global economy today is dominated by giant corporations, sovereign wealth funds, and nation-state monopolies – all ‘multinationals’ in a world economy. An economic proposition follows: ‘you can socialise capitalism, but you cannot capitalise socialism’ – at least for long – and the United States, Britain, Russia and China prove the rule. (Since no economist has taken up the ism and proposition, I call it Jencks’ Law).

My thought-experiment is that Singapore is one of socitalism’s greatest exemplars. Seen from its five public goods it looks like an exception to the rule of political inaction and failed promises, and one with the lowest rate of corruption in the world (after Denmark, according to Transparency International). Doubters of this narrative may find exceptions to the exceptions, and architectural ones can point to some fast and cheap building – often the rule in Asia. Yet in the larger social balance sheet, over 50 years the Three Ms also have proved generally positive: industrial Modernisation, social Modernity and cultural Modernism (the last, still mostly to come).

Diagram 2 Charles Jenks essay

Faustian bargains and balance sheets

There is, however, the usual price to be paid. As writers such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe well understood, and as he dramatised in 1831, all forms of capitalism entail creative destruction and a balance struck between many such polarities. In his theatrical poem Faust: A Tragedy, the Three Ms of progress lead inexorably to a trade-off, the legendary Faustian bargain with the devil. Here there is a surprising parallel with Singapore for, in Act Five of the German drama, the older Faust becomes a developer involved with the planned improvement in the lives of his subjects. This involves land reclamation, the building of dykes and dams to push back the sea (20 per cent of Singapore has been created this way, a key government policy). But Faust has to destroy a venerable chapel that gets in the way of progress, and remove an old couple (who are accidentally killed, as the devil over-interprets Faust’s instructions). The tragedy almost ends with the hero Faust blinded, and dying – but then, in another reversal, his soul is wafted to heaven by well-orchestrated angels, where the drama finally closes with a triumphant wilderness garden of nature. It has lovely gorges, green forests, desert cacti and rock outcrops, which disclose the parable of nature returned – a kind of botanic garden as born-again jungle – ever a staple of Germanic, romantic hope.

Diagram 3 Charles Jenks Essay

It is pushing the parallel a bit far, yet in the 1960s Lee Kuan Yew led the city-state towards progressive development with the tough, pragmatic maxim, ‘poetry is a luxury we cannot afford’. And to ensure economic development, a lot of freedoms and choice were postponed into the far-off future. But there are curious and positive parallels with the Germanic myth. Lee insisted the concrete jungle, which had to be built quickly, should become a new Garden City and then the ‘City in a Garden’, with an ever-increasing real jungle of tropical plants. Thus, the Botanic Garden, which the British had started in the 1850s, was to burgeon on reclaimed land into the Gardens by the Bay of 2012. As we will see, other positive-sum bargains followed, reminding us that although Faust ended tragically, he also ended as a kind of Germanic hero.³

Diagram 4 Charles Jenks essay

Diagram 5 Charles Jenks essay

Comparing bargains is to compare balance sheets and weigh how much one loses and gains. With Singapore that means thinking about its rare status, as one of three or four major city-states in the world. Compared with Western versions, I find it a more dynamic and interesting place than Monaco and Luxembourg, and (in some ways) the Vatican City (especially if you are a Protestant). In other ways, Singapore has a more creative population than Qatar, Bahrain, Abu Dhabi and Dubai. Western sceptics point out that Washington DC is itself a military city-state, not controlled by its country, and that London is a financial city-state independent of Britain. There is much (inconclusive) proof for both propositions, as with any thought-experiment, but today the idea of city power is certainly on the rise. The top 50 global cities are wresting back sovereignty from their national political leaders who, it appears, have lost control of housing and urbanism, ecology and economy, lost control of migration and public services. From the perspective of disconsolate Europeans, the city-state with its effective control has important lessons to teach the world. Moreover many city mayors and architects dream of having the Singapore’s Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) – with some real authority.

‘Bigness is no longer part of any urban tissue. It exists; at most, it coexists. Its subtext is: fuck context’

Alan Choe, former chief planner of URA, explained to me how effective this body is compared with planners elsewhere. Because it can, with the government, create land (as I mentioned, a key policy) it can control and increase its value. So it can also entice (or force) developers to do its bidding. Economic incentives are attached that reward developers who build in green measures, along with the other social goods that are mandated as part of their bargain. Hence the balanced public wealth that has grown over 50 years: progress by implicit social engineering. Again, it is a Faustian bargain that leads to a benign social contract between the government and the people. (In the wager are such things as the world’s second-largest gambling casino, a private development by Las Vegas Sands that, in effect, subsidises public projects – and, above all, the Gardens by the Bay).

Diagram 6 Charles Jenks essay

The social contract is implicit like the British constitution, but reaffirmed by the re-election of the People’s Action Party (PAP) which has not lost in 50 years (a world record of some sort). When its majority goes down to 60 per cent positive, as it did in 2011, PAP quickly responds to the popular signal – the social contract is, for the moment, highly interactive. Other cities of the world may try to practise such urban enticements for the public good, but they often fail because Western politicians are underpaid or corruption leaks into social contracts, and the bureaucracies are too big to manage (or as the saying goes, the banks too big to fail).

What is Generic Individualism?

One part of my gedanken is the question, how can Singapore, or indeed any global city, take the next step from its style of benevolent bigness, that is Generic Individualism? This curious opposition of words, I would argue, is the reigning international style of our time, one that dominates large corporations, big buildings and the global marketplace. It has three defining aspects. First of all, its hybrid or oxymoronic qualities combine the generic universalism of Modernism, the mass production of bigness, with the individual uniqueness sought in Postmodernism. Generic Individualism synthesises both movements and agenda. Second, the oxymoron is prevalent today because of a widespread social desire for identity, and the technologies of mass-customisation. These last were prophesied by Marshall McLuhan in 1966 as the true revolution of the electronic age given that the computer, he said, could produce 60 different Ford exhaust pipes as quickly, cheaply and efficiently as 60 similar ones. The social desire for more personal and ethnic expression also became a world movement in the 1960s. So, the third defining aspect is the contradictory style of big, repetitive, anonymous, abstract, mass-produced boxiness of universal Modernism and the individualised, varied, plural, mixed, ornamented, iconic, evocative feeling-enigmas of Postmodernism. Generic Individualism’s success and failure follow from these three defining aspects and suggest a further evolution.

The first part of this equation is bigness, the mutation in scale of late capitalism that affects the art market as much as the architectural, the increasing competition for prestige sites and big commissions. In 1990, ‘startists’ such as Damien Hirst began to say the most important artistic qualification today is to become a brand, a proposition that has been fleshed out with the 50 top brands commanding 95 per cent of the global market – soon followed by the churning out of extra-large canvases and sculptures, those by Jeff Koons and Richard Serra, or any leading artist bad or good.

‘Money isn’t everything and market pluralism is not the real thing’

For architecture, Rem Koolhaas put his finger on some consequences of ‘bigness or the problem of large’ in his heavy tome (weighing six pounds) called S,M,L,XL. This set the style for later ‘immersive’ publications by followers, who did not try to win an architectural argument so much as drown the viewer in a stew of images and a stream of selfies barely resembling thought. Koolhaas’s insights were the best of this XL convention, even peppered as his book is with non sequiturs and gratuitous nudity. Bigness starts with a large typeface theorem – ‘Beyond a certain scale, architecture acquires the properties of Bigness. The best reason to broach Bigness is the one given by climbers of Mount Everest: “because it is there”. Bigness is ultimate architecture …’ and then his typeface starts to shrink along with the thought, till it reaches theorem 5: ‘Together all these breaks – with scale, with architectural composition, with tradition, with transparency, with ethics – imply the final, most radical break: Bigness is no longer part of any urban tissue. It exists; at most, it coexists. Its subtext is: fuck context.’

Diagram 7 Charles Jenks essay

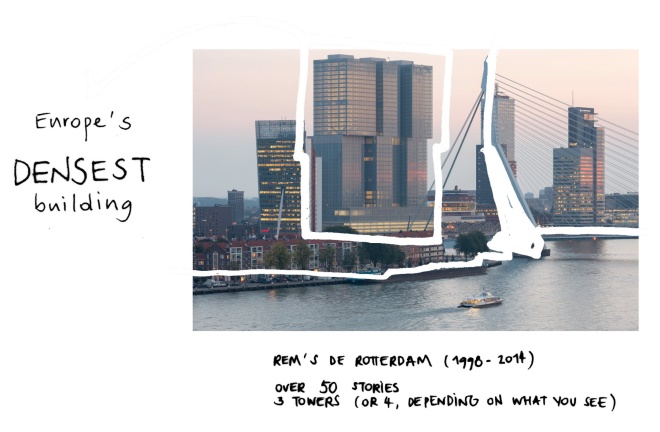

The poetic anger (or delight?) of this italicised verb is particularly damning when you compare what Bigness does to Koolhaas’s own biggest building, De Rotterdam, a series of three towers that are staggered and cut slightly to break down their oppressive size, and put above the usual base of mixed uses. In the original design of 1998 the generic curtain walls are tweaked just enough so they individualise the differing functions – offices, residences, hotel space and so on. So with the original design, Generic Individualism was resisting the horrors of massification and densification, at least a little. However, in the built reality, Bigness has really fucked not only the urban context but Koolhaas’s architecture itself, as the masses were smashed together to save more money (a constant theming of Bigness), and the variety of mullions was turned into the repetitive curtain walling (to save yet more). The result is the virus Monothematitis that spreads all over the original distinctions, and art. This amnesiacal homogeneity confirms his Theorem 3, that ‘honesty’ and ‘iconographic needs’ are impossible with Bigness – a classic case, familiar with Le Corbusier, where your own pet theory can be the most devastating inducement to your own architectural suicide.

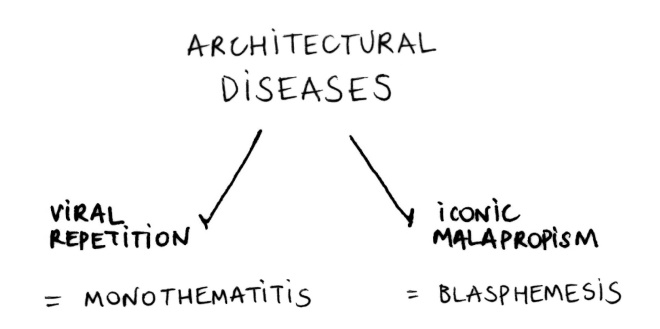

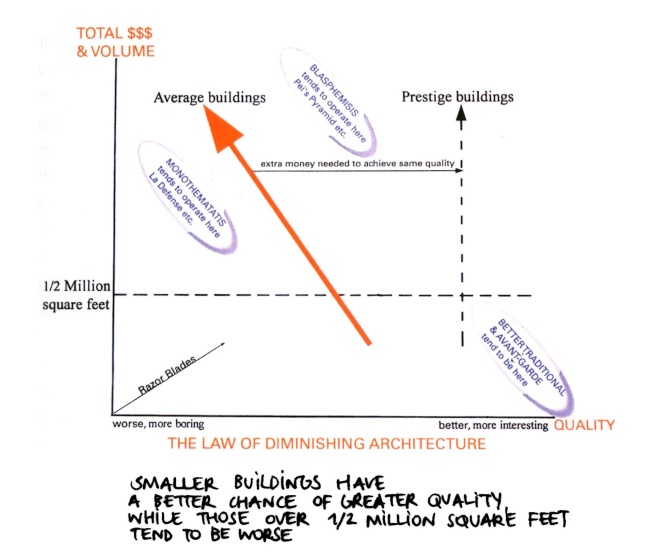

The law of diminishing architecture

It would be cruel to look here for further proof of Theorem 5. Indeed, Koolhaas might grant the asset stripping of his design by Big Finance; moreover there is much to admire elsewhere, in his good architecture and polemic. Besides, my point is to generalise about Bigness as a social and architectural tendency, or statistical rule of thumb. This I did in a 1975 chart showing the 10 connected reasons why Modernism died (and Postmodernism rose). They all interrelated closely with reason six: the great size of projects under late capitalism, those that became ‘too big’. How big is that? Obviously, as I wrote, there is no easy answer to this – 50 storeys? Or 100 storeys? Or a million square feet? Or both, like the Empire State Building? Like all social laws, it depends on a few changing variables such as technology, cost of land and culture. But the law of diminishing architecture can be formulated as a size generality, as in all sorts of fields where the limits of size are studied – for instance, in biology where the size of an animal is constrained by food and skeletal strength, in flying airbuses where the number of passengers and lightness of metals create limits, in skyscrapers where wind loads, lift speeds and investment returns curb height.

Diagram 8 Charles Jenks essay

So, for the ‘average building’ of bulk and height (above half a million square feet, or 50 storeys), the law of diminishing architecture shows a decline in the quality of the environment and architecture. The graph (page 59) shows the typical decline with increasing size over 50 storeys; however, if the developer or client wants a prestige building (far right) and pays much more money to achieve it, the law will bend under the weight of cash. The typical case is that above this limit in, say, New York, bigger means worse. Economies of scale that usually work turn into diseconomies of quality.

This is because bigger, above a certain size, usually means that all sorts of constraints of safety, economy, risk taking, conformity, stereotyping – the generic run amok – cut into the budget and strip the building (as in De Rotterdam). Razor blades (lower left in the diagram) along with Ford cars proved the Modernist paradigm case of economies of scale that ‘more and bigger means better’. That is true up to a tipping point with mass-produced objects, and why the generic has such a powerful relevance in global production today. But razor blades and automobiles are not megadevelopments. The latter, when they get ‘too big’, suffer from Monothematitis, a disease of runaway iteration, or Blasphemises, a disease of accidental iconography communicating the wrong message. The first illness was diagnosed by the historian William MacDonald, a plague in Roman architecture, which again shows the affinities of that style with our generic building. But what about the other disease of Bigness, the one that makes most large iconic buildings just icons to Mrs Malaprop’s horrendous (and enjoyable) stupidities?

‘You can socialise capitalism, but you cannot capitalise socialism’

Iconic architecture – hatred, love and blasphemy

You have to have a sense of humour failure not to laugh at all the failed icons sprouting up in every global city, like London’s ‘Walkie Talkie’, unless you are too distressed and just scream. All these reactions, as I argued in The Iconic Building: The Power of Enigma (2005), have been normal since Gustave Eiffel launched his capital company and tower of 300 metres on the people of Paris in 1887, and was met by a chorus of fury from the cultured and powerful. Typical insults were ‘it would destroy Paris’ and claims, from every quarter and journal, that this ‘American commercialism’ would dishonour the nation of France. The Committee of 300, the great and the good, fought it every metre of the way up. The building had no major function or use (unless, as cynics observed, to observe German armies invade), no iconography of meaning beyond the utilitarian one of rising up for a view, and was called all sorts of things including the ‘the world’s most expensive hatpin’. All this is well known and the story that, by 1900, in a violent shift in mood, hatred turned to love and the enigmatic signifier became, by 1910, not only the symbol of Modernism but the symbol of Paris and France itself.

Diagram 9 Charles Jenks essay

The lesson I drew from this for starchitects, on the way to designing ever-bigger icons, was to ponder hard the multiple meanings of enigmatic forms, map them onto natural or cosmic meanings, avoid one-liners, work hard – and pray to the great goddess: creativity. Still there is no guarantee, after the decline of metanarratives, such as religion, that your grand gesture will be loved. All icons, in the age of pluralism, inspire that little Bolshie iconoclast lurking in our heart and, positively, iconoclasm of a friendly sort is essential to democracy. Finally, if the Eiffel Tower is the ultimate paradigm for success, the exception that shows one rule at least – the question becomes, ‘is your icon risky, or hated, enough to become loved?’ There must be some paranoid charge and creative edge for the icon, in order to overcome the usual slide into stereotype (or the Walkie Talkie, or whatever malaprop damns the failure). There are rules and risk involved, changes of mind, exploration by a culture as it zigzags down the hill of precipitous interpretation. You have to feel your way and oscillate in opinion – I certainly do – when confronted by the largest in-your-face icon of Singapore.

Singapore’s unmissable icon

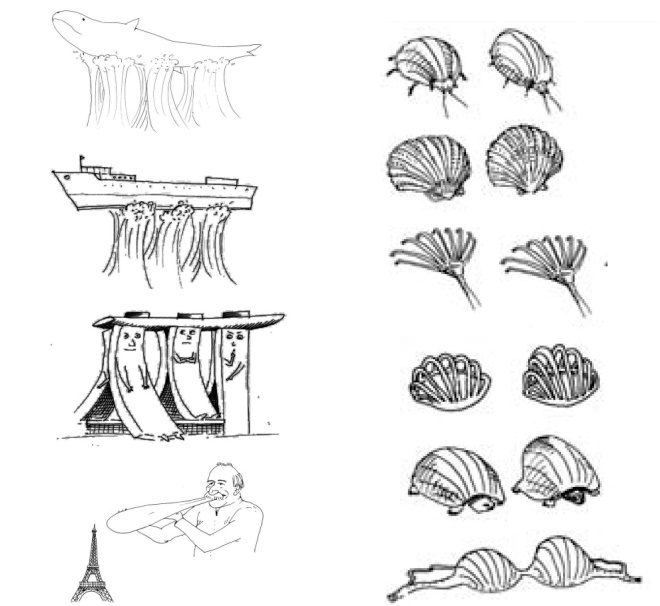

The iconic status of Moshe Safdie’s Marina Bay Sands is confirmed every day (by those who can’t see it, that is) by BBC World as the intermittent backdrop for broadcasts from South-East Asia. As a gateway to China and eastern trade, it faintly resembles a torii gate, ‘an open window’ for planes and ships as they pass and look out of their window or porthole on the way to the largest ports of Asia. The icon, as a firm T-shape with high closure, can be reduced to a letterhead and still be recognised (one necessity for the iconic sign). As an enigmatic signifier it certainly suggests many things without naming them: surfboard is the number-one metaphor that rolls off the lips, in order not to mention the other one that everybody perceives (like Foster’s ‘Gherkin’, some things are too obvious for polite company).

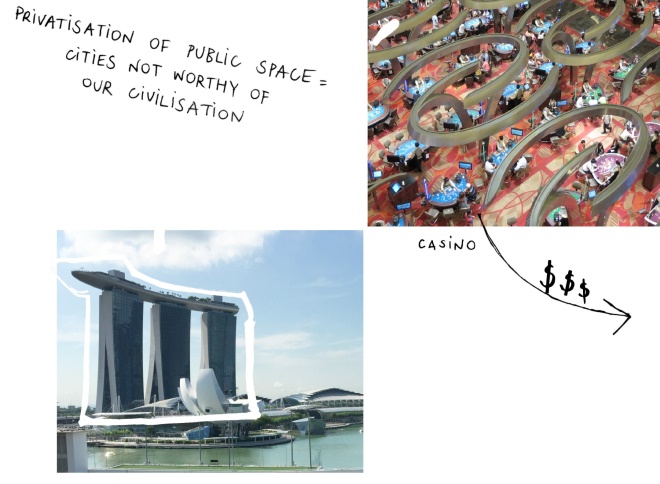

The developer Las Vegas Sands built this $5-billion extravaganza, which was nudged in social directions by the co-funding government. They called it ‘the world’s most-expensive standalone casino’ (after Macao) and ‘an integrated resort’. Some integration, some resort. It has two theatres, a convention centre (for four simultaneous conventions), countless upscale shops and restaurants, two malls, the ArtScience Museum and a wide promenade looking over the new, freshwater lake (with grand water pavilions for Louis Vuitton). If the Bigness of 750,000m2 is joined at the top by the surfboard or ‘killer fish’, it is pulled together at the bottom by a high curving atrium straight out of John Portman, a stereotype of every upscale hotel since 1965 – but here somehow much more Portmaniacal (up it zooms and curves, 11 storey-trays diminishing in perspective tilts, something that drove the engineers crazy with mass-customisation).

‘Icons will always elicit iconoclastic reactions, and so they should’

However, it really is the rooftop above the 57th floor, the SkyPark, that makes this the gateway to Asia (and has led to many jobs there for Safdie). Le Corbusier’s idea of a garden on the roof has been inflated to 2.5 acres and, according to comparisons by the developers, it is not only ‘340 metres long – longer than the Eiffel Tower laid on its side’ (which they lay on its side above the SkyPark, in case you doubt this statistic) but ‘it cantilevers out … 65 metres’ – yes! over 200 feet of surfboard riding over the cloud-waves in the sky … ‘Make no little plans’, the American planner of cities Daniel H Burnham advised in 1907, ‘they have no magic to stir men’s blood …’ The blood here is stirred, not shaken, by the solidity and size of the world’s longest infinity pool, the row of palm trees and the many amenities you couldn’t even imagine. However grotesque and ridiculously expensive it seems at first, the magic and logic start to eat away at doubts the more you visit this view. If you are going to put in the generic observation deck overlooking the heart of a city, then make it 100 times the size of the pathetic Rainbow Room atop the Rockefeller Center (‘Make no little plans …’).

‘It looks hard for Singapore and the global city to go beyond the reigning style of Generic Individualism’

Frankly, I more or less hated Marina Bay Sands when I saw it in design, photos and actuality, the first three times. And I found Safdie’s justifications (audible on Google and readable on Dezeen, 2014) hard to believe. He describes heroically resisting the competition brief that Las Vegas Sands and Singapore set up, as they asked for a single wall tower: ‘Symbolically that would have been unbearable, so I proposed three towers … a big window to the sea … you can see either way through the building to the other parts of the city’ [well, it is better than De Rotterdam, but you cannot see either way, unless you are 15 metres above casino level].

Safdie continues with positive ideas of public space: ‘It’s all about rethinking and proposing a new kind of public realm, which is contrary to the dominant typology of a cluster of towers sitting over a mall [De Rotterdam? or the malls of Singapore?] turning its back on the rest of the city.’ So far, so positive, were it true. But the public realm, he says, extends to the podium roof, whereas in fact it is more private, like a gated community, and vetted, and you pay to get into the SkyPark. Undeterred by such realities, Safdie admonishes us that the privatisation of public space is creating cities that are ‘not worthy of our civilisation’ and then goes on to fault architects for designing icons today that are conceived ‘as singular, independent sculptures. They think about towers as great sculptures, twisting this way, twisting that way …’

Diagram 10 Charles Jenks essay

It is hard to believe, with the three Marina Bay towers ‘twisting this way’ and the whole icon being like one gigantic sculpture, that Safdie could say such things (as if the developer had not advertised it as a standalone sculpture). But I believe Safdie believes his words, not only because I have heard him speak them in the past but because – relative to the Bigness paradigm – they have a truth, relative though it may be. Moreover, having disliked this whole development and having been in it for several conferences over those years, I hate to say that, in spite of my feelings and better judgement, I am starting to like the whole ‘integrated resort’. As a virtual gateway to Asia, it is more interesting than the Generic Individualism of the downtown skyscrapers, and more than a one-liner (if still stereotyped).

Icons will always elicit iconoclastic reactions, and so they should. But as scepticism and dislike wells up, remember the Eiffel Tower – count to 300 – and visit the area if you can because, in yet another example of the Faustian bargain, Marina Bay Sands has paid for the more-convincing icons just to the south.

Singapore is an orchid?

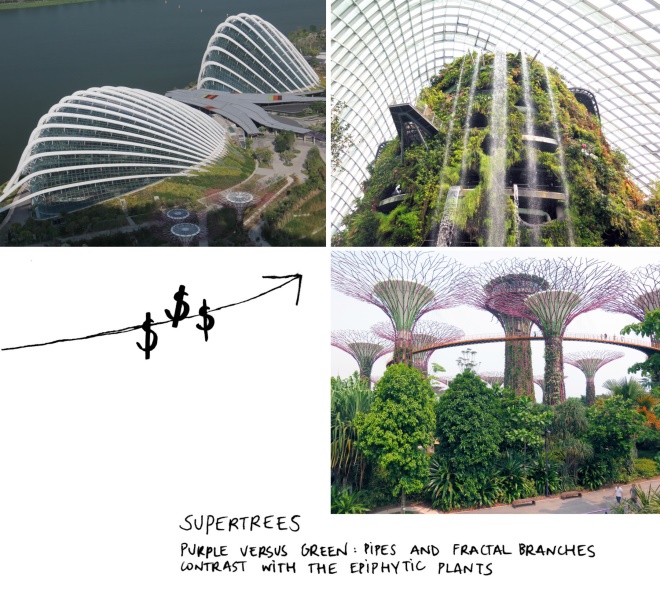

The Gardens by the Bay and its two ‘domes’ designed by Chris Wilkinson have textbook examples of the enigmatic signifier among their many wonders. For one thing the domes are not domes – but then odd expressive shapes are always seen in terms of their nearest stereotype. These varying ovoids are actually a set of parabolic arches, often bending in tension, that hold an inner gridshell of mullions and glass, also in tension. They are not circular, and not in much compression like the generic domes over 2,000 years. Rather, the parabolas fan about in concertina, sometimes lie near the ground in tension, or spring up to a pinched curve and do all sorts of handstands in order to function well, to aerate the greenhouses, to protect the plants as a sunshade and to achieve multiple goals, above all becoming the stunning white leaves of a giant orchid. According to the layout by Andrew Grant, these two shapes are the bottom petals of the orchid site plan (the orchid being the traditional symbol of Singapore), the footpaths and links are the stem, and the ‘Supertrees’ and main gardens the orchid’s flowers. All this is evident from the SkyPark, from exhibits inside the domes, and 50 metres up in the Supertrees. For once in an iconic project, the symbolism is more than a one-liner, taken seriously enough to be resonant with other meanings. But more of this iconological depth later – let us return to the metaphors of the non-dome domes.

Diagram 11 Charles Jenks essay

From one angle they look like ‘clam shells or tortoise shells’, from another like ‘black bulging eyes wearing protective white sunshades’, a ‘fan-shape of exoskeletons’, or ‘two garden rakes’ of different shape or – the oddest simile – ‘the asymmetrical reinforced bra of Madonna’. All of these overtones displaces the generic shape and, like the mixed metaphors of Shakespeare, add to the visual charge. Several variations are functional – the steep sides are by the east reservoir, thereby opening more generously in the west to visitors; also this individualising tilt creates a heat stack, venting the hot air effectively. End-pinches give the generic ellipses increased personality as well. In plan, the oval is slightly pointy or a warped vesica piscis shape. Compared with Foster’s ‘Armadillo’ domes in Glasgow or Gehry’s spinnaker domes in Paris, Wilkinson plays his metaphors in a utilitarian way. They are torqued and squeezed for both functional and aesthetic reasons – a successful icon often carries such a deep but precise ambiguity.

Inside the Mediterranean Flower Dome (the wider of the two) is a spectacular landscape of colours and growth, planted on several levels. The rhetoric of flowering plants – ‘Burgeoning Bromeliads in the Tropics’ – is, in Singapore, a kind of realistic fantasy or Chelsea Flower Show made permanent. As part of the national narrative it is meant to inspire the green revolution through sensuality not preaching, a paradise garden to delight as a form of what they call ‘edutainment’. The lower glasshouse here creates the cool-dry climate of the Mediterranean and the marvel is in the mixtures: the palm trees set against cypress and rioting roses, red-hot pokers and superabundant borders, a sea of yellow chrysanthemums that you climb over and around. It feels a bit like a composed wilderness painted by Le Douanier Rousseau, or nature’s mad exuberance carefully fine-tuned, in this case by the skilful hands of Dr Kiat W Tan and his fellow professionals. The results are horticulturally rare and sustainable.

Diagram 12 Charles Jenks essay

The taller fan-shaped building centres on a cloud forest of steaming epiphytic plants. Here the horticultural pilgrim is pulled up an artificial mountain of wild orchids, fuchsias and begonias, which seem to grow miraculously in mid-air (hydroponics of course). In the past, for instance at the Imperial Palace of Beijing, visitors would climb up through fantastic bullet-hole rocks, supposedly carved by Mother Nature. There the extraordinary sculpture and plants growing through it represented the Land of Immortals, a version of heaven depicted as much in Chinese art as in vertical rockeries. Instead, here you ascend the Cloud Forest ‘dome’ by lift, and the scaffold is a concrete cone not nature’s sculpture. Then you slowly descend on ramps that cantilever way out, forcing a good look at the artifice, and walk under waterfalls to absorb lessons in sustainability (here the edutainment is explicit, on didactic video). Mist is helpfully sprayed to further dazzle and confuse the senses (and water the forest). It is Disneyland Improved, by ironic learning and sustainability. The bread-loaf shape is reminiscent of Quelin in China, or the verdant peaks of Vietnam, or the Sacred Mountains in China – all stereotypes of travel and the fabulous.

Generic this may be, but what lifts the experience a notch is the way the narrative is sustained from the buildings into the adjoining gardens. The basic idea, as mentioned, is to use the exotic pleasures of nature to fight global warming – its emblem called Wild Orchidism – the beautiful crazy growth upon growth of the tropics. This iconographic programme extends throughout the greater landscape, thanks to Andrew Grant and Dr Tan, with its green and purple Supertrees. Eighteen of these artificial parasols range from 25 to 50 metres tall, with the tallest treehouse holding a restaurant. Biofuel reactor below, food above, surrealism overall. The Supertrees may recall the vertical green walls of Patrick Blanc, but here they become giant fractal climbing frames for the ultimate epiphytic landscape, the artificial rainforest Singapore is trying to resurrect. In this sense the iconographic programme epitomises Singapore’s transformation into the City in a Garden, the idea of greening that started in the 1960s, and which, since the 1980s, has become more systematic.

‘You have to feel your way and oscillate in opinion when confronted by the largest in-your-face icon of Singapore’

Sustainability is, of course, both a global piety and very much part of the iconic arms race in architecture and in places such as Masdar City, Abu Dhabi, where Foster’s ecological plans are slowly progressing. In all cases a trade-off pits high-cost investment against green morality, economic bigness versus ecology. Singapore looks like one of the few cities to have squared this circle. It has used social engineering to make developers do the right thing or, at Marina Bay Sands, the private casino to the north to subsidise the public oasis to the south. What appears on the balance sheet? The ‘integrated resort’ takes in money that pays for the freshwater marina on the city side, and the reservoir and gardens to the east and south (about $1.5 billion, and still counting) – three, huge public projects.

I have heard that the integrated resort makes between $5 billion and $35 billion profit per year. Who knows? But in 1965, the American architect Charles Moore wrote a Faustian polemic about Disneyland: You Have to pay for the Public Life. Here the ‘you’ means the government of Singapore, which apparently paid for 80 per cent of this overall project (and reaps many of the benefits it passes on to the public). Thus Singapore Inc, unlike most of the world today but like Ancient Rome in the past, manages to balance some books. It enhances the individual and private corporation to pay for the generic and public commonwealth.

Real artistic personalisation?

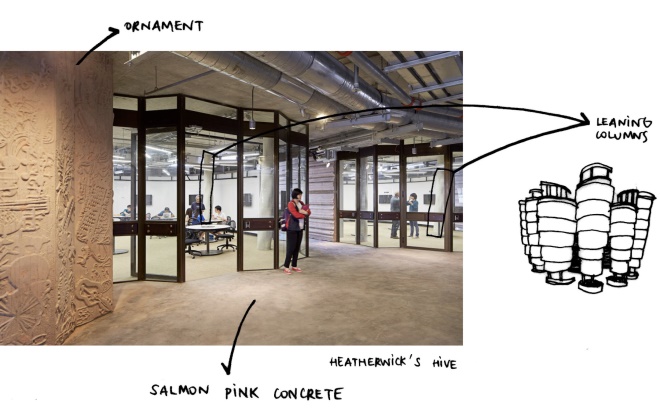

It looks hard for Singapore and the global city, however, to go beyond the reigning style of Generic Individualism. One reason is because, as the law of diminishing architecture sets in, bigness tends toward impersonal compromise. But some young designers, such as Thomas Heatherwick, are trying to become less generic and more personalised, going beyond generic mass customisation. Heatherwick’s building for Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University – The Hive – is a case in point, with its three personalising moves, all of which are carried out with great energy and conviction.

First are the iconic shapes – the 12 telescopic pods or ‘dim sum baskets’ as they are known – curved pods that step up and loom out, each slightly different from the next. Such friendly forms and associations are appropriate for breaking up mass learning into smaller self-organising groups, a requirement of the client. The second strategy for giving more place and identity is the way the concrete striations, and voids for ventilation, are varied. These are also nicely syncopated in outline against the sky, giving a picturesque profile and movement, carefully composed to face the approach – a road up a hill. On the inside, the salmon pink concrete and the tilting, carved columns give a further welcome differentiation. The third element of mass customisation is particularly evident in the 1,000 concrete panels. Working with the artist Sara Fanelli, who combines complex patterns, Heatherwick says the result ‘makes a soulful building that gives love to concrete’.

Fanelli draws many ‘thought triggers’ or ‘mind doodles’, and then varies the plastic moulds slightly so they look as if they were the mark of time, and individual intent. Yet a doubt sets in with these variations: the results are still impersonal, and one reason is that there is no overall message for the distinctions to signify, no narrative to follow, no iconographic programme as there was in the Gardens by the Bay.

Diagram 13 Charles Jenks essay

As Ruskin and others have long pointed out, real artistic freedom consists in freely interpreting both material and meaning, or spontaneous variation guided by a purpose. Here the ornamental panels are more like randomised differentiation and less like personal cuisine. In effect, they are the consumer choice offered by market pluralism, or choosing from a set menu. This is the kind of difference one sees in the Emirates, the way Dubai will order a Hadid or Gehry or Koolhaas – ready-made-off-the-shelf. It is better than no choice or Fordism (‘you can have any Ford, as long as it is black’), but it is not yet real artistic creativity emerging from within, for instance the work of Le Corbusier or Antonio Gaudí. Heatherwick has gone a half-step beyond the reigning individualism but he has not reached full artistic personalisation.

A hint of transformation

In a sense The Hive personifies the larger situation, the city’s intention to move towards a fuller freedom rather than its realisation. Singapore has reached the crisis of its perfection, and not only the perfectionitis mentioned by Liu Thai Ker. Positively, it has pushed a rare single-mindedness of public purpose further than other city-states, not to mention other nations. Its policies of public health, education, transport, planning, housing, a clean water programme, re-wilderness, ecology and a lack of corruption work probably as well as, or better than, they do in other states (it is hard to say ‘any other’, as statistics are not available). However, its architecture and art programmes, which remain at a high level of generality, have yet to go to the next level, which may prove hard. The reason is shared with global cities and the Gulf States, which can gentrify and move towards a cultural programme – and the iconic building – but find the open society and the freedoms of opposition a step too far. Singapore has hints of such a transformation that it could well afford but is unsure how to take.

Gardens by the Bay is the one obvious exception where Singapore has created, as New York City did in the 1850s, a world-class Central Park. This will be the public heart of its urban future, surrounded by more buildings as further land is reclaimed and built upon. For me, the exceptional creativity here is a result of the rare interaction between the architects, designers, landscapers and botanists on one side, and the client on the other. Both sides rose to an agenda and iconographic programme worth signifying. To take risks, produce quality and sacrifice your time, you have to have something worth doing; Singapore provided this to the garden designers, in effect the ‘re-wilding of a tropical city’. I don’t believe good architecture is possible without the simultaneous commitment of such a client and designer around a shared agenda and symbolic programme, but that is a subject for another time. Generic Individualism is better than generic reproduction, but to go beyond this will take a shift in outlook that is now only just beginning.

Endnotes

1. For some of the journalistic debate see William Gibson’s ‘Disneyland with the Death Penalty’, first published in Wired, Sept/October 1993, and its many responses viewable on the internet including Rem Koolhaas’s ‘Singapore Songlines: Portrait of a Potemkin Metropolis, … or 30 Years of Tabula Rasa’, in S,M,L,XL, first published by the Monacelli Press, New York, 1995, pp1008-89. A critical response to both, by the Singaporean Tang Weng Hong, is What is Authenticity? Singapore as Potemkin Metropolis, 2005. A good recent overview of Singapore at 50 years, from which I have drawn, is the special report from The Economist, ‘Singapore: The Singapore Exception’, published 18 July 2015. Quotations from Lee Kuan Yew have also been taken from this publication.

2. See ‘Singapore, Capital City for Vertical Green’, A&U, special issue, 2012, p37.

3. ‘Singapore: The Singapore Exception’. Special report, The Economist, 18 July 2015.

The Architectural Review An online and print magazine about international design. Since 1896.

The Architectural Review An online and print magazine about international design. Since 1896.